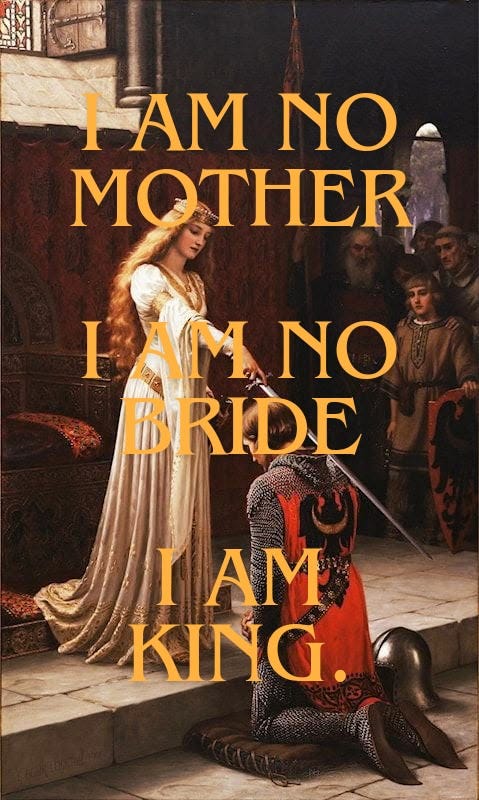

The Mother

feminine archetypes and relationships

In a recent bout of self-doubt, I took an internet quiz to find out which feminine archetype I am. I love a personality quiz or really anything that will tell me who I am and why I am that way. I’m a Sagittarius sun, Sagittarius Moon, Capricorn Rising, ENFJ, Enneagram Type 4, thanks for asking, but none of these are surprising to me. My result on the Feminine Archetype quiz, however—The Mother—is.

I took the quiz twice and got The Mother both times. The first time I saw the result I thought, that can’t be right. I mean, I haven’t changed a diaper since that time I got norovirus from a baby I was nannying in, like, 2015. So I tried to change my answers the second time, but sure enough.

The general consensus on The Mother archetype is that Mothers are loving and nurturing with warm and supportive energy, but they can struggle with boundaries and codependency. The “light side” of The Mother makes me feel great about myself. The Mother “profoundly understands unconditional love,” “cares deeply for those around her,” “gains great satisfaction from being able to nurture others,” and “is the most heart-centered archetype.” All of this feels true to me if you’ll allow me to toot my own horn.

That “shadow side,” though…damn. The Mother “often puts others before herself—she forgets to fill her own well and struggles to set boundaries.” Drag me, random internet personality quiz.

This is absolutely true of me and is also absolutely my fatal flaw. It’s why I’ve repeatedly found myself in one-sided and unfulfilling relationships. I fall in love easily, tend to see the best in people and ignore the bad, and care deeply about others’ feelings, often to the detriment of my own. I stick around way longer than I should, even when I’m miserable, out of a sense of obligation. I have encountered this in some friendships with women, but mostly I have encountered it in romantic relationships with men.

I am still studying CJ Hauser and their boundless wisdom. They know what I’m talking about.

“There is a kind of man I tend to date,” Hauser writes in the essay “The Lady with the Lamp.”

“This man is considered undatable by the more reasonable public.

He is considered difficult. He is the sort of man who, when you say his name, those who have met him say, ‘Oh, him.’ He is known by everyone in broad strokes and intimately by no one. He seldom has many close friends. He is eccentric or ornery or sad. He is a loner but also has a big mouth. He does not like many people. He does not let people get close. If you date this kind of man, and meet a friend or relative of his, without fail, they will say, ‘We’re just so glad X finally found someone!’ and there will be an edge of disbelief or perhaps relief in their voice.”

Several examples of how and why I relate to this:

When I was 21ish I dated a guy I met on Bumble who, when I dragged him to meet my friends, quite literally sat at the picnic tables of various sunshiny breweries in complete and total silence. Like, he didn’t utter a word to my friends other than the initial “Hello.” Like, didn’t even follow it up with a “How are you?”

Before that, I dated a guy I met at the summer camp I worked at. He and most of the other counselors had grown up going to the camp together, but I was a blow-in. So, when this guy showed interest in me and I showed interest in him back, more than one of the counselors pulled me aside to say, “You know no one likes him, right?”

In my last relationship, I went to my partner’s family Thanksgiving, where his various relatives were surprised and delighted by my presence because he’d never had a girlfriend. As we were leaving, an Aunt said she loved meeting me and joked that she might like me more than him. An Uncle, who had been billed to me as the scary one, literally said, “I do like you more than him.”

In that first example, after we broke up, one of my best friend’s boyfriend told me he never liked the guy, and I told my best friend’s boyfriend that he had to tell me stuff like that at the beginning from now on because this man is a golden retriever type who likes everyone, so if he doesn’t like someone that person is probably a sociopath. The point here is that every man I’ve been in a relationship with has been considered difficult and/or undatable and/or just plain strange by my friends and family as well as most strangers.

But if I’m being honest with myself, even if my best friend’s boyfriend (now husband and baby daddy, incidentally), whom I think so highly of, told me he didn’t like the guy I was dating before things got too serious, I probably wouldn’t listen.

“The average person, when encountering such a man, will think, Oh, boy, and keep a distance. They will not have figured this man out, per se, but the fact of the man seeming mysterious, seeming to have something up with him, is not a thing that is intriguing to them. They do not feel the need to find out what is up. They have a suspicion that, whatever is up, it will not bring them joy or peace to know about it. And for this reason they go no further.”

My best friend’s husband and baby daddy, as well as my other best friend’s husband and baby daddy, as well as my mother, father, sibling, the mailman, the bartender at my favorite brewery, and the guy who runs the front desk at the gym and only ever wears cutoff company-branded t-shirts to show off his muscles, could all tell me the guy I’m dating isn’t a tortured poet with a heart of gold but, actually, just a sad weirdo who will probably ruin my life, and still I would be like, “He just needs someone like me to bring him out of his shell! Even sad weirdos deserve love!" because I am The Mother.

“Meeting this kind of man activates an impulse. It is not lust. It certainly isn’t love. It’s the sense that someone has fallen by the wayside and I am the only Samaritan around who might stop. That perhaps by virtue of noticing or being intrigued by him, I am uniquely suited to helping—practically obligated, in fact. I can save this man, I tell myself.

My method for doing this is by dating him.”

Hauser, I would bet, is also The Mother. They call the belief that they can help these men who have not asked for help narcissistic, and I’m inclined to agree, though I also believe (or have convinced myself) that even if it’s narcissistic to think (or hope) I possess such a power, the impulse of wanting to help is sincere and, I hate myself for saying this, selfless.

But being selfless in this situation is the problem because the person who ends up hurt is always me—myself—and the man in question rarely leaves the situation a different, cured person (there was that one guy in high school who I totally pulled a Queer Eye on, but I digress). So, who am I really helping? And where did I get this idea that helping is akin to loving?

“For years, I have convinced myself that love is meant to be an act of extreme and transformative caretaking. And so I’ve been more savior than partner. More robot than girl. More nurse than lover.”

Hauser refers to their savior complex as “Florence Nightingale Syndrome” after the famous nurse who “is credited with creating many of the methods that spawned uniform modern nursing practices” and also for falling in love with her patients. This inspired the “syndrome” or “effect” named after her in storytelling, “in which a caregiver falls in love with their patient, even if there is very little real exchange between them. Caretaking is conflated with love and so the syndrome takes hold.”

Turns out there is no historical evidence of the story about Nightingale falling in love with her patients, shocker, but that isn’t important to the point I’m trying to make. What I care about is this:

“The thing about the Florence Nightingale Syndrome is that it doesn’t imply that women should stop taking care of people. Rather, it looks at this devoted, persistent care and says: All that is fine so long as you don’t feel a way about it. By the effect’s logic, the way female care goes from saintly to disordered is when a woman develops an emotional relationship with the object of her care or perhaps even with the idea of care itself. The disorder is not being able to devote yourself to this kind of caretaking without having feelings about it and thereby becoming distractingly human.”

Those darn feelings again. Men famously hate those.

This has been the dynamic in all of my relationships. Sad Boy needs taking care of, I’m happy to do so, I start to develop an emotional attachment to Sad Boy and the things he says and does, I let Sad Boy know, Sad Boy is all, “Huh? You have feelings? Feelings about me and my actions?? How dare you. Please leave me alone,” and I’m like, “Say what now?” and on and on until either Sad Boy asks me to leave his apartment or vice versa and then we never speak again.

Before you ask—no, I don’t have abandonment issues. My parents are still together and very much devoted to one another. I live with them, actually, in the house I grew up in. My childhood was safe and supportive and loving. And so why am I like this? “Perhaps,” writes Hauser, “to enjoy being the hero who swoops in and saves the day is to have a deep desire for self-annihilation.”

"Saving someone feels easy, compared to asking yourself who the hell you are and what you want and how you want to be loved and by whom. Compared to asking, How might I care for myself?”

I’d like to think I know who I am and what I want (or at least what I like), and by now, I at least know how I don’t want to be loved, but I definitely don’t know how to care for myself. I have gotten by my whole life by being agreeable to the needs and desires of others, rarely stopping to figure out my own. And to be fair to me, hardly anyone else has asked either.

The sick ouroboros of this whole thing is that I think I developed the habit of putting others’ needs before my own because too many of the people who have claimed to love me (to be clear, not my family members) have loved me precisely for my caretaking abilities—my Mothering—while ignoring my needs or forgetting I had them all together, and I have called that love because that’s what they told me it was.

But that was a lie. I don’t know what that is, but it isn’t love. I’m not sure I would know how to let someone take care of me if they tried. I fear that, at this point, I would perceive care as danger.

The best I can do is look to my friendships for examples of what makes me feel cared for, like when Halli hugs me while I cry in a bar and licks my ear to make me laugh, or when Mackenzie and her husband/baby daddy invite me on their family excursions, or when Ruth calls me on a random Thursday to ask how I’m doing, or when Caite feeds me and welcomes me to her dinner table with her family. Somewhere along the line, I forgot that those things are acts of love, too.

That you are Mother surprised me zero.

You're wonderful and I'm loving these essays. Yes CJ, Yes Florence, Yes Emma Chance.